The IMF report Embedded in Nature (October 2024) is a small revolution in the world of macroeconomics: it introduces an original conceptual framework in which Nature is at the heart of the economic system. This will hopefully encourage national and international institutions to rethink their usual modelling tools, whose structural weaknesses have been demonstrated time and over again.

You can read the french version of this post here

1. The many flaws in macroeconomic models

Macroeconomics, as an academic discipline, routinely sustains severe criticism. It is sometimes done in a diplomatic way, like when Nobel Prize winner Paul Romer admits it makes him feel « disturbed »[1], while sometimes researchers are more direct, like when Steve Keen bluntly denounces a “failure”[2]. Other criticisms, such as Hyman Minsky’s, are indirect, insisting that despite recurring evidence, most of these models do not even allow for the possibility of endogenous financial crises, as such crises would simply be at odds with their underlying « general equilibrium » analytical framework. As for behavioural economists, they have shown that economic agents are not rational in the sense that such models presuppose, which significantly undermines their realism. Finally, it is notorious that no economist or institution using these models had been able to predict the 2008 financial crisis.

This contestation of the pertinence of macroeconomics also shows through a relative disaffection with the discipline and a renewed interest in empirical economics (also motivated by the growth in data processing capacity) and other disciplines such as ecological economics. Yet, as described in two recent papers by the Chair Energy and Prosperity on IAM models[3], these macroeconomic models are still widely used by governments and by key global institutions and are a determining factor in the conduct of economic policies, be they budgetary, fiscal, monetary or commercial.[4]

Let’s look at a few examples of how important these models have become. The budget trajectories of EU Member States produced by the European Commission as part of the EU economic governance are calculated using rather rustic versions of these macroeconomic models, based on a Cobb-Douglas function[5]. In France, budget forecasts are produced using such models, like the Mésange, Opale (and the tresthor platform) and Saphir ones.

As another example, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), a network of central banks and financial supervisors, which is studying the impact of climate change on financial stability, uses several of these macroeconomic models (Remind, Message globiom, Nigem)[6], despite their well-known limitations, as described above[7].

The World Bank also relies on numerous hybrid models, notably in its initiative to equip a coalition of finance ministries – the Global Macro Modeling Initiative[8] (GMMI) – and in its assessments of countries’ climate policies, the Country Climate and Development Reports (CCDRs[9]).

These models also play a central role in the work of the IPCC, which aims to provide an economic assessment of the consequences of global warming and/or measures to limit it. In the report Finance in hot house world (2023), Thierry Philipponnat, Chief Economist at Finance Watch, pinpoints the problem: « With the world’s current climate action, our planet is on the road of a +3°C average temperature increase: It is becoming a “hot house world” where more than 3 billion people will have to “adapt” to progressively uninhabitable living conditions. Yet policymakers’ economic models predict only a benign level of economic losses from such climate impacts. The cause of such an obvious quantification problem is that the theories behind these economic models rely on backwards-looking data, make assumptions about economic ‘equilibrium’ and use damage functions that are not suitable for modelling an economy disrupted by climate change. Most importantly, the impact of climate change resulting from economic modelling is not compatible with climate science. Yet, the climate scenario analyses conducted by financial supervisors all use these models.”

Let us clarify that the present analysis is not about judging the efforts made by researchers and practitioners to improve their modeling work and respond to criticism, but to highlight the biases generated by the use of reference models in actual public policies. It should also be remembered that the topic of environmental macroeconomics is in full effervescence, and that it is not possible to account for all these dynamics[10].

| The limitations of « dominant » macroeconomic models Most of these models do not include the role of money or finance, despite their decisive impact in economic terms (as demonstrated by Hyman Minsky, quoted above); 1.Many do not take into account the interactions between nature and the economy; 2.some do so by using damage functions (climate to the economy) which greatly underestimate the damage; 3.Most make the (false) assumption that artificial capital (machines) can replace « natural capital » and labour without limit; 4.Most are based on a production function used to estimate GDP and its variation, who is supposed to measure an economic cost if it is negative or an increase in wealth if it is positive. This supposes adding an arbitrary parameter of total factor productivity, the relevance of which is really debatable, which makes GDP partially exogenous, and therefore in fact partially independent from the impacts of climate change;[11] 5.The state is often absent; 6.Returns are considered to be diminishing or constant, which is contrary to the economic reality; 7.Some model a closed economy, with no international trade (or exchange rates); 8.Many are equilibrium models in the neoclassical sense: the trajectory necessarily converges towards a single equilibrium; 9/The diversity of economic agents is usually not represented, which means that social inequalities are not either; 10.None of them includes tipping points; 11.Most of them are based on ad hoc calibrations and are not backtested; 12.The behaviour of actors is assumed to be « rational » in the neoclassical sense; 13.The results of modelling are generally very sensitive to the choice of discount rate (which reflects a greater or lesser preference for the present), which is basically arbitrary. For more details on the above problems, which are common to macroeconomic models used in large institutions and to IAM models[12], please consult the Working Paper Les modèles IAMs et leurs limites (IAM models and their limitations) (2024). The same working paper also introduces « coherent stock-flow » models[13] (Coherent in financial terms and in terms of natural resources), which aim to remove some of the above limits (in particular the limits listed as number 1, 2, 8, 10 and 12) and the IF initiative (by Carbone 4, which focuses on biophysical limits and their evolution). |

We seem to have reached an impasse: the tools we use for economic reasoning on the biggest issues of our time (climate and the destruction of biodiversity) are unreliable.

We use them because they are the only ones approved by the most academically recognised international economic journals, which gives them institutional pre-eminence and thus reinforced by the influence of the economists[14] who prescribe them or use them.

We also use them for the apparent intellectual comfort they bring by being able to provide figures that maintain an illusion of control, and finally because of the high cost (and time required) of developing new tools.

To get out of this impasse, we need courage and the willingness to wipe the slate clean of these tools. We can therefore only warmly welcome the IMF report Embedded in Nature: Nature-Related Economic and Financial Risks and Policy Considerations (2024), which takes a first step in this direction.

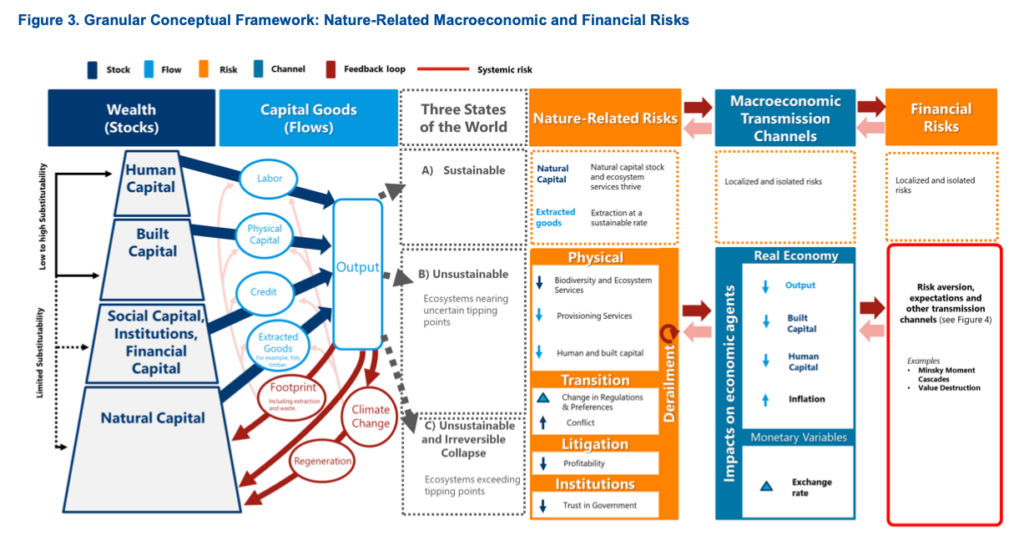

This IMF publication proposes a new conceptual framework[15] (see diagram below), within which, for fundamental reasons explained below, most of the economic models used by institutions today cannot fit.

We will first present some of the most noteworthy advances described in this work, and in the second part we will propose extra ones, that we feel should be made to complete this revolution (whether or not they are implicit in the IMF publication).

The new conceptual framework proposed by the IMF

Source: Embedded in Nature: Nature-Related Economic and Financial Risks and Policy Considerations (2024). Page 7

This diagram is presented as follows (page 5):

« We propose a conceptual framework to analyze nature-related risks and their feedback mechanisms. Drawing on the Dasgupta Review, the macroeconomic framework features four main components (Figure 3). First, it connects the four types of capital (nature, social, produced, and human) to economic and financial flows. Second, it relates these flows to potential states of the world based on production sustainability over time (sustainable, unsustainable, and irreversible collapse), with the last two approaching or exceeding natural capital’s tipping point, risking irreversible damage. Third, it describes the main nature-related risks associated with each state of the world. Fourth, it maps out macroeconomic transmission channels linking nature-related risks to the real economy—including impacts on quantities and prices—and vice versa, and the financial sector, emphasizing the “double materiality” principle whereby financial institutions both affect and are affected by nature-related risks (Figure 4).”

2 The IMF report: a rupture with mainstream economic thinking

A. Nature and economics are of two different orders

Human beings are part of Nature. The history of the planet is intrinsically linked to the appearance of life and its evolution, and vice versa[16]. The profound and spectacular interactions between living and non-living organisms[17] are increasingly well known[18]. We also know that the human species, the fruit of 4 billion years of co-evolution, now has a decisive impact on the conditions of habitability of our planet for the human species as well as for the majority of living beings[19]. We are now on the verge to take the planet out of the range of variation of certain parameters[20] which would make it inhospitable to life as a whole.

However, Nature and the services that « we derive from it » are not economic goods for three fundamental reasons:

- Nature does not charge. Economic exchanges take place between humans and the entities they control.

- Nature has a use value for us, but above all it has an intrinsic value, and it is quite simply a condition for human life.

- The irreversible destruction of Nature and the overstepping of planetary limits have no equivalent in economic terms; money is created ex nihilo[21] from accounting entries and then circulates, and human labour is more or less reproduced year after year.

Trying to « bring » Nature into the economy by « internalising externalities », monetising the value of ecosystem services, treating Nature as « economic capital » is a « theoretical power grab » that must be abandoned.

It is implicitly based on equivalences that cannot be made: the postulate of « weak » sustainability or sustainability according to which artificial capital (machines) can replace natural capital[22] has become lethal.

This assumption, the fruit of our feeling of omnipotence based on our technological ‘successes’, is totally illusory. All we need to do to convince ourselves of this is to take a close look at the incredibly complex and subtle interactions at work in ecosystems. As the report states (page 25), quoting Dasgupta[23]:

« The substitutability between natural capital and other forms of capital is limited. There are “little-to-no substitution possibilities between key forms of natural capital and produced capital and for that matter any other form of capital« .

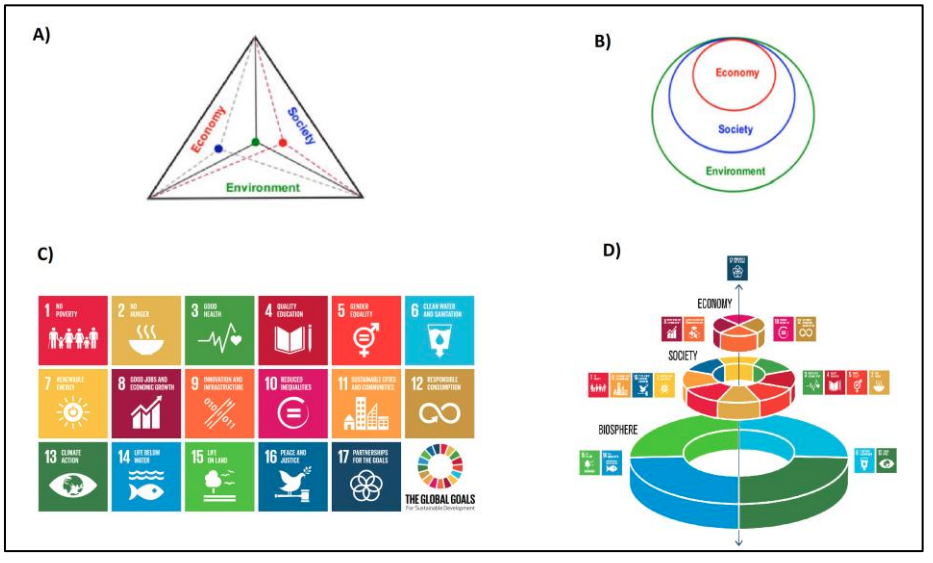

Strong and weak sustainability

« The weak sustainability approach (A) looks at the total sum of capital, including social, manufactured and natural capital, while the strong sustainability approach (B) puts maintaining the environment in a good state as an essential condition of sustainability. We can apply this representation to the sustainable development objectives (C), where the achievement of sustainability is based on the good state of the four environmental objectives (D).”

Source: La soutenabilité forte comme paradigme pour faire le lien entre économie et science de la durabilité, Adrien Comte, IRD (2023)

Abandoning the postulate of « weak » sustainability has many consequences, which are not explicitly mentioned in the IMF report but which it is important to come back to. In particular, it means rejecting the monetisation of ecosystem services as such. This doesn’t necessarily mean to ignore the consequences of their use nor the economic costs of their destruction or « repair/restoration »[24].

This also leads us to reject the use of the « cost-benefit » reasoning for issues as crucial as climate change or the destruction of biodiversity.

It forces us to think carefully about the necessary evolution in accounting, both private or public. Under no circumstances should Nature be considered as an asset (= comparable to any other, from the point of view of financial return).

In business accounting, it could possibly be considered as a liability: this is the option taken in the « multi-capital accounting » approach[25] which is currently in full swing, although it cannot be said today that it is the best solution from an accounting point of view.[26]

In public accounting, it is dangerous to suggest that countries should measure their wealth by including not only physical capital (such as infrastructure) and human capital (education, health), but also natural capital. This is what was proposed by the World Bank when it developed the adjusted net savings or « genuine savings » indicator, which is calculated for France by INSEE[27]. Of course, these adjustments show a value for public assets that is lower than we might think, since when we include the deterioration due to the effects of climate change, public assets lose some value. But the results are highly dependent on the monetary values used to make these adjustments (which are debatable and necessarily based on models). The use of this indicator opens the door to trade-offs between « capitals » that are not acceptable in a logic of strong sustainability. Take just one example: a hectare of « natural » forest in France will always be « worth » less economically than if it could be built on[28]. To protect forests from the need to build or from economic appetites, regulations are needed.

B Global limits and ecological tipping points are at the heart of the conceptual framework proposed in the IMF report.[29]

As we have just seen, human activities are pushing certain vital parameters out of ranges that have been self-regulating for millions of years. These are known as planetary limits. The emblematic case is that of the atmospheric concentration of CO2, which now exceeds the concentration reached 3 million years ago.[30]

The processes that are set in motion are non-linear and can lead to major disasters when what scientists call tipping points are reached, i.e. thresholds which, once crossed, cause the natural system concerned to run out of control.[31]

Economics is incapable of modelling, let alone putting a price or an economic value on such a complex system. The reasons for this are both axiological (it is not its job to do this) and methodological (economics doesn’t have the tools to do this). The fundamental problem stems from the confusion, among most neoclassical economists, on what comes under economic analysis and what comes under ethics or politics. Since Léon Walras, this line of thought has been normative[32] in the sense that the descriptive dimension of the economic system is accompanied by public policy recommendations. It is important to distinguish between the two.

To put it another way, the problem of limits is by definition part of a dogmatic framework, in the sense given to it by the jurist Alain Supiot[33]. It is this framework that legitimises institutions, standards, public prices, the division between the public and the private, the commons, and so on. The relevant framework for thinking about the problem of limits is therefore that of political and collective decision-making, and not the restricted analytical framework of economics. Economics can only intervene once the framework has been established.

This new conceptual framework leads us to propose public policies in terms of internationally accepted prohibitions and not just in terms of negotiable objectives. The IMF note explains this position as follows:

« In theory, it should be possible for societies to define a set of essential values, including the conservation of nature and the reversal of biodiversity loss, on which citizens can unite. A corollary of such an agreement would be prohibitions on nature-destroying activities, akin to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, the current United Nations negotiations on deep-seabed mining regulations, and laws that prohibit human trafficking and other illegal activities.«

It is the acceptance of planetary limits that underpins the need for the precautionary principle[34], which continues to be misunderstood as a principle of inaction or anti-innovation, when its aim is quite simply « not to play the sorcerer’s apprentice ».

C. We must abandon the use of aggregate production functions to project GDP and of damage functions to assess the cost of climate change.

The macroeconomic models used by international institutions (and those whose results are summarised by the IPCC) use aggregate production functions. The relevance of this representation was criticised very early on, in what economists refer to as the two Cambridges controversy of the 1960s. This is an important economic debate that took place in the 1960s. In short, on the one side, Samuelson and Solow (MIT, Cambridge, USA) defend the idea of the possibility of a single measure of capital. On the other, Robinson and Sraffa (University of Cambridge, England) point out that capital is made up of a heterogeneous set of physical assets (machines, buildings, etc.), the monetary measurement of which depends on relative prices and the rate of profit. This makes prices both an input and an output of these models, since it is these models that enable these relative prices to be calculated, making the underlying economic reasoning self-referential.

The ‘critical’ point of view, embodied at the time by Joan Robinson and Piero Sraffa, was undoubtedly the most coherent, something that even Paul Samuelson (who along with Robert Solow opposed it) came to recognise. This is now widely accepted[35], including by influential economists, such as Jeremy Rudd[36], a member of the Fed Board.

Their remark, technical in nature, turns out to be fundamental to the representation of interactions between the economy and Nature. On the one hand, if it is difficult, if not impossible, to aggregate elements of physical capital in a coherent way, it is even more so for different types of “natural capital” and a fortiori for the total of the two, which is done in the weak sustainability perspective.

On the other hand, GDP projections are indeed made on the basis of these production functions. As these production functions have failed to reflect the real evolution of GDP, they have been « completed » by a factor, the Total Factor Productivity (TFP), about which Jeremy Rudd writes that « even the most carefully constructed estimates of total factor productivity will be meaningless« .

In most macroeconomic models, this TFP is generally set at around 1 to 2% per annum[37]. This suggests that GDP will continue to grow exponentially whatever the state of the planet.

When economists try to assess the impact of global warming on GDP growth, they calculate a damage function that links a certain level of increase in global temperature to a loss of GDP. This damage function is then used to correct GDP growth in a « reference scenario » (in which global warming does not exist), which is calculated using the method described above, i.e. with growth of 1 to 2% per year, forever.

Thus, as stated by the NGFS in its 2024 report on damage functions[38]:

« The world economy is expected to grow by more than 300% by the end of the century (i.e. more than quadrupling). Even assuming a much more conservative growth rate of 1% per year, the world economy is still expected to grow by more than 120%. The 30% loss[39] must be interpreted in the light of these basic growth figures.«

The massive bias introduced by this type of modelling is easy to understand: as long as we assume that GDP will grow exponentially throughout the 20th century, the losses in GDP linked to global warming (which are drastically underestimated at this stage) do not even lead to a recession. Note that the same method is used for ecosystem services[40].

We can therefore only welcome the position set out in the IMF note:

« Despite the widespread use of the aggregate production function in macroeconomic models, we opt not to use it because of its lack of robust theoretical and empirical foundations. At the theoretical level, it has been shown that the aggregate production function is simply an accounting identity to measure aggregate value added, and does not contain any information on technological relationships in the economy (Rudd 2024, Shaikh 1974, Simon 1979). Indeed, Fisher (1971) shows that the supply side of the economy can only be described using a production function under highly unrealistic conditions. Empirically, Shaikh (1974) and Fisher (1993) show that the fit with the data provided by an aggregate Cobb-Douglas production function with constant returns to scale, for any data, is a mathematical consequence of constant factor shares, an empirical result that is simply due to a law of algebra. Regarding total factor productivity (TFP), Rudd (2024) notes that “labor and capital aggregates that are relevant to production can only exist under conditions that are unlikely to ever be met by a real-world economy,” meaning that “even the most carefully constructed estimates of total factor productivity will be meaningless.” For these reasons, we do not introduce an aggregate production function or TFP in our framework. »

As for the damage functions linking global average temperature growth to GDP, they are questionable (and criticized) for two fundamental reasons. Firstly, their estimation is based on economic models that are incapable of taking into account the complexity of ecosystems and the effects of their current degradation on the economy. Secondly, since the impacts of climate change and the collapse of biodiversity are non-linear and subject to ‘tipping points’, it is impossible for economists to project these functions into a significantly warmer world.

The IMF note (page 6) warns quite clearly about the limitations of the estimates published to date on the impacts of climate and ecological degradation on the economy, and gives several explanations, including the following: « A key reason is the inability of models to represent complex interactions between ecosystem services, and between ecosystem services and the economy. Most models are skewed toward capturing selected ecosystem services that relate to the provisioning of food, water, and bioenergy[41]”.

D. Productivity must be redefined

According to most economists, a country’s economic growth (GDP per capita[42]) is the result of growth in the productivity of the factors of production[43], due to scientific and technical progress and progress in the organisation of work. As we have just seen, economists[44] model this progress using a TFP, whose estimation is, strictly speaking, impossible.

But the notion of productivity poses a deeper problem that the IMF note highlights. To put it simply, it is supposed to result from « ungrounded » mechanisms, i.e. without taking into account the pressure on ecosystems.

As a result, the authors of the notes write (page 28):

« we define productivity as the efficiency of production subject to the preservation of the material basis for the creation of economic value, which encompasses nature. This definition implies that an increase in labor or capital productivity that is associated with nature loss or degradation is an apparent productivity gain rather than an actual one (that is, it overestimates productivity gains), as it has an adverse impact on the material conditions on which economic value creation itself depends. »

This reconsideration of productivity goes further than the abandonment of production functions just mentioned. It calls into question the « dominant paradigm » according to which we must always increase productivity in order to increase the wealth produced and, consequently, the satisfaction of each and every one of us.

We approached this subject from a slightly different angle in a recent article[45], in which we argued for « non-market values » to be taken into account, as well as the productivity of natural resources in the broad sense, to take account of the potential scarcity of these resources. Tomorrow’s economy must become extremely parsimonious with regard to its « consumption of Nature » and must stop trying to optimise the output of human labour and/or its « equipment » without taking account of Nature’s limited capacities, including its capacity to reproduce.

E. The assumptions behind free trade must be challenged

In the IMF note’s, the analysis of difficulties and sometimes impasses for some developing countries calls into question the theoretical virtues of free trade.

Here is an extract (Annex Box 1. page 39):

« Developing economies often rely heavily on nature-degrading exports to obtain foreign exchange, as noted previously. Given the productive structure of these economies and the nature loss embedded in their economic activities and particularly in their exports (Dasgupta and Levin 2023[46]), ultimately one of the consequences of repeated shocks and sovereign and external debt crises will be to increase investments in, and lock infrastructure associated with, nature-loss-inducing (as well as carbon-intensive) activities. For instance, growth in export oriented soy production and mining—largely aimed at addressing balance of payments needs—has led to deforestation and nature loss in Argentina and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, respectively (Dempsey et al 2024[47]). Although efforts are being made in the global governance on nature and climate to take into account these linkages and domestic constraints tied to the international monetary and financial architecture, more needs to be done.”

This analysis, where developing countries accumulate external financial constraints – from risks of lock-in in economic models to the effects on Nature of the resulting economic choices – takes us a long way from the idealised views of international trade relations found in standard economic analyses.

F. Some public policy proposals are expressed in mostly qualitative terms, calling into question certain dogmas.

The note makes a number of public policy proposals. Here are a few examples.

1 In theory, it should be possible for societies to define a set of essential values, including the conservation of nature and the reversal of biodiversity loss, on which citizens can unite. […] An institutional change of this magnitude would impose limits on the actions of financial institutions (page 19).

2 A rapid, orderly phasing out of harmful economic activities […], policies, and financing (page 22).

3 Recognize the systemic effects of crossing planetary boundaries and the existence of biophysical tipping points (page 23).

4 Build social and political consensus on transitioning away from non-sustainable economic activities. Second, there is a need to reorient policies to prioritize the rapid transformation of the productive structure of the economy to align with planetary boundaries. (page 23).

5 Further research […] the implications of nature loss for debt sustainability, […] the role of domestic economic and financial constraints related to the international monetary and financial architecture in locking countries into nature-degrading growth models [and the development of] the concept of a “nature Minsky moment” (page 24).

It is clear that these proposals could not have been the result of a standard initial « framing »; they are not the result of a cost-benefit analysis, but are expressed in terms of limitations on activities, of profound interactions between Nature and the economy that cannot be captured by reasoning in terms of negative externalities.

2. Further progress to be made

The IMF note marks substantial progress, but we believe it is crucial to go even further.

A. Robustness versus optimisation

Neoclassical economists are accustomed to thinking in terms of optimisation (of an intertemporal utility function, a cost-benefit trade-off or a cost-efficiency trade-off) on the grounds that the very purpose of economics is to optimise the use of scarce resources[48].

Once we recognise (paragraph 1.A above) that the economy cannot correctly represent the functioning of ecosystems, even though they are decisive in the production and services they provide, it is illusory to seek an economic optimum. What is and what will be the optimum for agriculture in southern Spain once this region is transformed into a desert? What will it be in regions where the « wet temperature » will be so high that it will be lethal for humans?

We agree with Olivier Hamant[49] who says that humanity’s quest for performance has produced the socio-economic crisis we are experiencing. We are going to live in a world that is increasingly fluctuating and uncertain. This is what life has been doing since it first appeared. How has it done so over such a long period of time? Not by looking for optimisations, but for robustness, which enables a stable system to be maintained despite fluctuations. For example, photosynthesis, which has existed for 3.8 billion years, has a « very low » energy yield of 0.3 to 0.8%. This low level of efficiency enables plants to manage biological and luminosity fluctuations, making them very robust.

In macroeconomic terms, this means that we should not be looking for optimisation, but for the capacity of our socio-economic systems to withstand future fluctuations.

This means that the « new economy » must focus on the safety margins in relation to planetary limits and look for indicators that define not a theoretical optimum but an acceptable and truly sustainable state. This doesn’t dilute, on the contrary, economic players’ duty to be as sober as possible and to reduce pressure on nature as much as possible, which presupposes to go beyond mere resilience through innovations in use and processes, and requires setting up dedicated incentives.

For this, we don’t need precise data (with 2 decimal places precision), but orders of magnitude. This primarily concerns the biophysical data that defines whether our ecosystems maintain their capacity to sustain human life and the socio-economic data that defines an acceptable social state – in terms of health, access to basic goods and services whether private or public, social inequalities (monetary and non-monetary, etc.).

B. Abandon GDP as an indicator of social well-being and its decline as a measure of economic cost.

Despite being under constant criticism over the last few decades and the important work carried out at the UN (with the SDGs) and in the wake of the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi report[50], GDP[51] continues to be the most important economic indicator. It is used, for example, to show that Europe is falling behind the United States. As this article in Le Monde puts it: « In 2008, the eurozone and the United States had equivalent gross domestic product (GDP) at current prices of $14,200 billion and $14,800 billion respectively (€13,082 billion and €13,635 billion). Fifteen years on, the Europeans’ GDP is just over $15,000 billion, while that of the United States has soared to $26,900 billion« . However, analysis of other indicators such as life expectancy, drug use, obesity and diet, investment in infrastructure, health spending per capita paints a far less glorious picture of the United States.[52]

Macroeconomic models that aim to compare the « economic cost » of climate action with that of inaction do so by comparing the loss of GDP generated in various scenarios. In this approach, the economic cost is therefore the loss of GDP. This is an extremely narrow understanding of the concept of cost, and it makes us lose sight of what is most important, as we explain in the fact sheet Qu’est-ce qu’un coût ? (What is a cost?) on the platform The Other Economy.[53]

It is time to abandon GDP as an indicator for this purpose: GDP is not relevant as a guide for these broad comparisons. More generally, cost-benefit analyses are only legitimate at the margin of a given economic situation, for example to compare two road or rail development options. But using them to compare two overall macroeconomic situations over long time horizons is illusory, if not inappropriate.

The evaluation of well-being and its evolution must be based on a set of socio-ecological indicators, such as health[54]. This is what the UN has tried to do by promoting the Sustainable Development Goals, albeit with two symmetrical flaws: an excess of indicators[55] and, conversely, an attempt to rank countries by adopting an aggregate score representing all the SDGs[56]. We need a synthetic dashboard, such as what was proposed by the SAS law in France[57].

This in no way detracts from the value of GDP for other purposes, such as calculating tax revenues or measuring market activity. It should also be well noted that acknowledging the limits of GDP doesn’t negate the fact that increases in income are correlated with a feeling of satisfaction – and conversely that poverty is never a positive experience. But for this particular end, Net National Income is preferable to GDP and it needs to be corrected through measures of inequalities in income and wealth[58], and by incorporating the redistributive effects of access to public services[59] and non-monetarized activities[60]. The INSEE has done a great deal of work in this direction, with the notion of augmented accounts. Here is the introductory word on its blog: “Today, the INSEE publishes the first augmented national accounts. This innovation aims to capture economic activity, its consequences for climate disruption, and the distribution of household income all in one place.”

The key point is to avoid above all reducing the assessment of a country’s situation to its GDP, or to assess the costs of action or inaction in relation to Nature in terms of GDP. We must reaffirm that we will not be able to generate GDP on a planet that is +5°C or lifeless.

C. Rejection of the dogma of general equilibrium and market efficiency

Although implicit in the text, the dogma of general equilibrium which underlies all neoclassical general equilibrium models[61] and DSGE is not explicitly rejected. Yet this dogma is not only contrary to the facts[62] but also dangerous, since it leads its supporters to believe that the economy spontaneously returns to equilibrium after a shock.

This is obviously not true as the great financial crises of 1929 and 2008 has demonstrated but above all, because of this belief, we don’t pay enough attention to the imbalances that are evident. On the contrary, we need to know quite clearly the margins within which our socio-economic system can operate (in terms of trade deficits, private and public debt, tolerance of social inequalities, destruction of nature, pollution, etc.) in order to deduce when public authorities need to intervene to allow the system to remain within these margins.

In this conception of market efficiency, some of the « failures » of the markets are recognised, as are the problems that result from them. But the ‘solution’ proposed to correct these failures is to put in place mechanisms, such as a carbon tax for climate change, which would allow the markets to solve the problems posed. Public authorities, ill-informed or under-informed, could not solve them any better. This dogmatic vision must be opposed. Even if markets are useful, they cannot achieve socially or environmentally desirable objectives without strong regulation and supervision by public authorities[63].

D. Instead of forecasts, using scenarios broadly outlining a possible future

The economic models we have just been talking about put a spotlight on quantification within a conceptual framework that has become obsolete.

We need attentions to focus on a whole new conceptual framework along the lines outlined in the preceding pages. The most effective method (and it is the one used by the NGFS) is to use scenarios to make us see and, if possible, feel what the possible futures hold.

But these scenarios should not be used to assess the costs associated with a climate drift or losses of nature. They should be used to check that the planetary limits are respected and under what conditions.

E. The use of biophysical modelling and ‘toy models’ for the economy

As we have just seen, the claim that models can reproduce economic data and project it into a world that is increasingly destabilised in ecological and social terms is vain. Nevertheless, it is useful to have simulations that are limited to a given question and a given time horizon. To this end, priority should be given to biophysical simulations[64] that allow us to explore the « distance to the limits » of the economy in various scenarios.

In addition, it is possible to use targeted models which are not intended to represent the entirety of an overly complex reality, but rather one of its aspects. They can be conceptual (known as « toy models ») or calibrated with empirical data, as are energy models, for example.

F. Linking ecological and social issues

Macroeconomic models are generally poor at representing social inequalities and poverty. They often use a “representative agent” supposed to represent an average individual, which is very simplistic and theoretically dangerous: the question of social inequalities and the societal impacts of both the transition and the physical risks of climate change and of the destruction of biodiversity are crucial. The IMF publication we comment on here also tells little about these issues. It reiterates (page 26) the view expressed by Dasgupta:

“Institutions and social capital play a critical role in determining individual and collective preferences, and therefore the economics of nature.

Institutions can be defined as “the humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic and social interaction,” consisting of “both informal constraints (sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct), and formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights)” (North 1991). They are understood to “support values and produce and protect interests” (Vatn 2005, p. 83). Economic policy decisions are shaped by institutions.

Social capital. Following Helliwell and Putnam (2004), social capital can be defined as the combination of mutual trust, confidence in governments and markets, and more broadly “the institutional arrangements that enable people to engage with one another for mutual benefit.” Trust, cooperation, and social capital form the foundation on which institutions rest. Social capital is therefore central to the economics of biodiversity (Dasgupta 2021, p. 165).”But these words are somewhat ethereal compared to the political and social violence that can be seen in certain countries, and which will be increased by ecological disorders.

It would no doubt be useful to explore the “Doughnut” approach initiated by Kate Raworth[65] and continued by the work of the Doughnut Economic Action Lab and Andrew Fanning, who are, to our knowledge, the most advanced on the need to take into account both planetary limits and social boundaries[66].

Conclusion

We have just highlighted and put into perspective a note from the IMF which we feel makes a significant step towards ensuring that the macroeconomics we need to steer our economies over the medium and long term take serious account of Nature and planetary limits. We have suggested a few ways forward.

The macroeconomic models and concepts discussed here are important because they shape, and are shaped by our leaders’ mental representations. Changing models is necessary, but obviously not sufficient to change decisions or even leaders’ inclinations. In particular, we have not touched upon strategic, institutional, democratic or cultural issues.

The work is far from finished, and it will require courage and perseverance in the face of the force of habit and acquired positions. But it is absolutely essential in the face of the perils we all face.

Alain Grandjean

This note has benefited from the constructive comments of Jean-Marc Béguin, Didier Blanchet, David Cayla, Louis Delannoy, François Meunier, Pierre Viard and Jean-Marc Vittori. I would like to thank them warmly for their contributions, and of course the final content does not commit them in any way.

Notes

[1] See the article Trouble with Macroeconomics, Paul Romer, 2016.

[2] See Steve Keen’s book Debunking Economics, Zed Books editions, 2011 and The New Economics: A Manifesto, Polity, 2021.

[3] See Alain Grandjean, Les modèles IAMs et leurs limites, Chair Energy and Prosperity, 2024 and Alain Grandjean and Gaël Giraud, Comparaison des modèles météorologiques, climatiques et économiques, 2017.

[4] The assessment of trade policies and the effects of free trade agreements is often based on macroeconomic models, some of which are computable general equilibrium models. The best-known example is the Global Trade Analysis Project model.

[5] See Fondement analytique et limites des règles budgétaires européennes on the platform The Other Economy.

[6] See Climate macroeconomic modelling handbook, NGFS, 2024

[7] See Alain Grandjean, Les modèles IAMs et leurs limites, Chair Energy and Prosperity, 2024

[8] See World Bank Group Macroeconomic Models for Climate Policy Analysis, 2022.

[9] See What You Need to Know About How CCDRs Estimate Climate Finance Needs, World Bank (13/03/23)

[10] One example of the dynamism of modeling in this field is Agent Based Models, which are increasingly used in this field. See Juana Castro, Stefan Drews, Filippos Exadaktylos, Joël Foramitti, Franziska Klein, Théo Konc, Ivan Savin, Jeroen van den Bergh, A review of agent‐based modeling of climate‐energy policy, Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 2020. And Francesco Lamperti’s work, see this article by Francesco Lamperti et al. Faraway, so Close: Coupled Climate and Economic Dynamics in an Agent Based Model, Ecological Economics, 2018.

[11] To find out more, read the article La croissance du PIB n’est pas expliquée par les modèles macroéconomiques les plus utilisés on the platform The Other Economy.

[12] Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) aim to help understand the interactions between human societies, economic development and climate over the long term. The assessment is said to be integrated because these models aim to describe both the economic system and natural systems by coupling modules representing the economy, the energy system and the climate (and sometimes other natural systems).

[13] These include the GEMMES model created by Gaël Giraud and now being developed by the team of economists at the AFD led by Antoine Godin. There is also the work of Yannis Dafermos (who co-developed the SFC DEFINE model) and Tim Jackson.

[14] Without going into an institutional analysis, which is beyond the scope of this note. See Pierre Alayrac – Les économistes, une noblesse d’Europe? Eu !radio, Nov. 2024

[15] It is based on a number of studies, including Sir Partha Dasgupta’s report The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review (2021), but the IMF report goes further than this, and sometimes even breaks with it, as we shall see here.

[16] See the book by Philippe Bertrand and Louis Legendre Earth, Our living Planet – The Earth System and its Co-evolution With Organisms, Springer, 2021. See also Les Attracteurs de Gaia, Editions Publibook, 2008, Philippe Bertrand.

[17] Be they chemical reactions, geological forces, the planet’s internal energy due in part to radioactivity, its magnetism, volcanism, plate tectonics, or the attraction of the sun and the planets of the solar system (from which results the precession of the equinoxes – limited by the presence of the moon – and the major climatic cycles), etc.

[18] Oxygen, the dominant gas in the air, is now indispensable and inseparable from life. However, it was produced by living organisms – who invented photosynthesis, which produces oxygen from carbon dioxide and water – in an environment for which it represented a violent toxic agent: the first living organisms were anaerobic and not equipped to resist its oxidising power. Oxygen production is a fact of life. In 2 billion years, the accumulation of stocks was sufficient to change the oxygen content of the atmosphere from 1% to 21%, the current level. The major cycles (carbon, phosphorus, nitrogen, etc. see the book Les attracteurs de Gaia) are all linked to interactions between living and non-living things.

[19] It’s not for nothing that Pope Francis speaks of our common home (see his encyclical Laudato Si).

[20] To take oxygen as an example, its proportion (21%) in air has been very stable for 10 to 15 million years (see Glasspool, I. J., & Scott, A. C. (2010). Phanerozoic concentrations of atmospheric oxygen reconstructed from sedimentary charcoal, Nature Geoscience). It is now proven that the current biosphere in turn ensures the chemical stability of our atmosphere. But its composition is changing as a result of our propensity to burn fossil fuels on a massive scale. And we also know that an increase of 2 to 3% in the oxygen content of the atmosphere would be enough, by multiplying the number of fires, to trigger sufficient instability to threaten our conditions of survival.

[21] Accounting entries are always balanced; money creation, which is a bank liability, always has a counterpart, such as a receivable. But the terms “created ex nihilo” refer to the fact that money is not always the result of a prior deposit. This being said, the monetary question is a complex one which deserves more than this succinct formulation. See the module “La monnaie” on the platform The Other Economy.

[22] This assumption is implicit in Robert Solow’s reasoning and his well-known criticisms of the Meadows report. To find out more, see the articles « La poursuite infinie de la croissance économique serait possible » and « Il suffirait de remplacer les ressources naturelles par du capital artificiel (des machines) » on the platform The Other Economy.

[23] Page 328.

[24] See Doit-on donner un prix à la nature ?, on the platform The Other Economy.

[25] See the work relating to the CARE framework and that of the Ecological Accounting Chair, and the module L’entreprise et sa comptabilité on the platform The Other Economy.

[26] There has been a great deal of discussion about changes to accounting standards and their application, but these are all technical and wide-ranging issues (accounting rules are mandatory for hundreds of millions of companies worldwide).

[27] See L’épargne nette ajustée des effets liés au climat est négative en France. Insee Analyses No. 98. November 2024. And Croissance, soutenabilité climatique, redistribution : qu’apprend-on des « comptes augmentés » ?, Insee blog, Nov. 2024

[28] The report L’approche économique de la biodiversité et des services liés aux éco-systèmes, commissioned by the French government in 2009, estimated that a hectare of natural forest could be worth €35,000 per hectare (by discounting the annual value of €970 per hectare), with a range of a ratio of 4 (between approximately €15,000 and €60,000). Building land in France is worth €100,000 per hectare on average.

[29] See Figure 3, p. 7, and Annex Figures 1.1 to 1.3, pp. 32-34.

[30] For around 800,000 years, the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere had stabilised at between 180 and 300 ppm. It now exceeds 400 ppm.

[31] Our climate, for example, has a number of tipping points which, once crossed, will trigger chain reactions leading to a runaway increase in global warming: ocean currents come to a halt, Greenland melts, continental glaciers melt, and so on. Similarly, biodiversity balances are complex, and a relatively strong increase in pressure can lead to a sudden collapse in the population of a species.

[32]Let us recall this well-known sentence: « M. Pareto believes that the goal of science is to get closer and closer to reality by successive approximations. But, I believe that the goal of science is to develop a certain ideal model and then to relate reality to that ideal, and that is why I have specified such an ideal” ». Auguste et Léon Walras, Œuvres économiques complètes, Vol. XIII. p. 567 (Walras L. Œuvres diverses) – Pierre Dockès, Claude Mouchot and Jean-Pierre Potier, Economica.

[33] In his book Homo juridicus, Essai sur la fonction anthropologique du Droit , Le Seuil, 2009. Here is an extract from the publisher’s summary: « The aspiration to justice is, for better or for worse, a fundamental anthropological fact, because in order to live together, human beings need to agree on the same meaning of life, whereas there is none that can be discovered scientifically. Legal dogma is the Western way of binding people together in this way. Law is the text in which our founding beliefs are written: a belief in a meaning of the human being, in the power of laws or in the strength of a word given ».

In this respect, Alain Supiot follows Pierre Legendre, who believes that in all societies, human reason has dogmatic foundations. See V. P. Legendre, De la Société comme texte, Linéaments d’une anthropologie dogmatique, Fayard, 2001.

[34] See Parer aux risques de demain: Le principe de précaution, Dominique Bourg and Jean-Louis Schlegel, Seuil, 2009.

[35] For an overview of the literature on aggregate production functions, see Felipe and Fisher, Aggregation in Production Functions: What Applied Economists should Know, Metroeconomica, 2003.

[36] A Practical Guide to Macroeconomics, Jeremy B. Rudd, Cambridge University Press, 2024.

[37] Recently, the figure has been slightly lower for developed countries, but higher for emerging countries, where TFP can be as high as 2 to 4%.

[38] See Damage functions, NGFS scenarios, and the economic commitment of climate change An explanatory note, NGFS 2024, page 29; and Climate macroeconomic modelling handbook, NGFS, 2024.

[39] This loss of 30% is the assessment adopted at this stage by the NGFS of the damage caused by climate change and evaluated using a damage function.

[40] Authors such as Giglio et al (Giglio, Stefano, Theresa. Kuchler, Johannes Ströbel, and Olivier Wang. 2024. The Economics of Biodiversity Loss CEPR Discussion Paper DP19277, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.) model the production of aggregate ecosystem services using an aggregate production function.

[41] Mathilde Salin, Katie Kedward, and Nepomuk Dunz. « Assessing Integrated Assessment Models for Building Global Nature-Economy Scenarios. » Banque de France. Working Paper No. 959. 2024.

[42] Demographics of course play a decisive role in the evolution of GDP, and this is a major issue both for the development of the least developed countries and, in the long term, for the relationship between mankind and Nature. But here, we are only dealing with the question of per capita GDP growth.

[43] The productivity of a factor of production (capital or labour, for example) is the ratio between the output produced and the factor used to produce it. In practice, labour productivity is easier to define: it is the ratio of hours worked to GDP.

[44] To simplify matters, there is a powerful school of thought, known as endogenous growth, which recognises that growth does not come from « nowhere », but can be explained by education, research and innovation. But in practice, because of the complexity of the subject and the difficulty of accurately measuring some of its parameters (such as the rate of innovation or the return on investment in human capital), the macro models used by institutions are based on production functions and TFP…

[45] Dépenses improductives, dette publique et création monétaire, Chroniques de l’Anthropocène, 2024

[46] Dasgupta, Partha and Levin, Simon, Economic Factors Underlying Biodiversity Loss (February 1, 2023). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B

[47] Dempsey, Jessica, Audrey Irvine-Broque, Tova Gaster, Lorah Steichen, Patrick Bigger, Azul Carolina Duque, Amelia Linett, and others. 2024. « Exporting Extinction: How the International Financial System Constrains Biodiverse Futures. » The Centre for Climate Justice, Climate and Community Project, and Third World Network, University of British Columbia.

[48] It should be noted here that, paradoxically, the accounting tools used in practice and mainstream economic models do not at all lead to an optimized use of natural resources, for the aforementioned reason that resources are not accounted for.

[49] See the TEDx La révolution de la robustesse and his book « La troisième voie du vivant » Odile Jacob, 2022.

[50] See the report by the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, 2009. Following the work of this Commission, the Mesures de l’économie chair, co-directed by Catherine Doz and Marc Feurbaey was created at the Paris School of Economics. See also the book by Marc Feurbaey and Didier Blanchet, Beyond GDP, Measuring Welfare and Assessing Sustainability. Oxford University Press, 2013.

[51] To find out more about GDP, how this indicator is constructed, what it represents and its limits, you can consult the module on PIB, croissance et limites planétaires on the platform The Other Economy.

[52] 37% of U.S. adults can’t afford an unexpected $400 expense on their own (they would have to borrow/sell something or just can’t afford it at all). See Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2023, Fed. In addition, 100 million Americans are mired in medical debt. See 100 Million People in America Are Saddled With Health Care Debt, KFF Health News, 2022. For a wider perspective on this, see also Etats-Unis : Pourquoi Trump ? 10 chiffres clefs sur une société cassée, Le Grand Continent (02/11/24) and Dette, inégalités, démocratie malade : des failles made in America, Alternatives Economiques (27/09/24)

[53] Readers interested in this topic will also find the following article on mitigation costs useful. Köberle, A.C., Vandyck, T., Guivarch, C. et al. The cost of mitigation revisited. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 1035-1045 (2021).

[54] On this subject, see Eloi Laurent’s book Et si la santé guidait le monde? L’espérance de vie vaut mieux que la croissance. Les Liens qui libèrent. 2021.

[55] There are 17 SDGs, broken down into 169 targets for the 2015-2030 period, and monitored at international level by 231 indicators (France tracks 98). See Indicateurs pour le suivi national des objectifs de développement durable, Insee (04/07/24).

[56] See the ranking of the world’s countries according to their overall score on the SDGs on the Sustainable report 2024 website.

[57] Passed in 2015 in France, the SAS law requires the government to submit an annual report to Parliament presenting the evolution of new wealth indicators, as well as an assessment of the impact of the main reforms undertaken with regard to these indicators. Following this vote, work began on identifying 10 wealth indicators. In practice, the reports made mandatory by this law have received no media coverage, and are neither known nor used by politicians.

[58] See the article Les inégalités monétaires se sont fortement accrues dans les dernières décennies au sein des pays développés and the Infosheet Comment mesurer les inégalités monétaires? on the platform The Other Economy.

[59] See the article La redistribution de richesses réduit les inégalités, on the platform The Other Economy.

[60] GDP does not include domestic work or voluntary work. Determining whether GDP should be corrected to include this or whether we should structurally give value to what has no price is a fundamental debate.

[61] Neo-Keynesian models introduce market rigidities in the short term but converge towards a general equilibrium in the long term.

[62] There are many reasons for this, which we can’t go into here (see on the platform The Other Economy the article Les marchés financiers seraient efficients), but one of the most important is not always mentioned. General competitive equilibrium theorems are based on the assumption of diminishing returns, whereas in most economic sectors, returns are increasing. In this case, competition leads to the formation of oligopolies or monopolies (economists use the term monopolistic competition, see Michel Volle’s book Iconomie) and does not lead to an optimum.

[63] See the report “Finance to citizens”, Secours Catholique, 2018

[64] This is what Carbone4’s IF initiative is doing.

[65] Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist (2017)

[66] See the website A Good Life For All Within Planetary Boundaries, where each country is analysed using the doughnut criteria, and the article Fanning, A.L., O’Neill, D.W., Hickel, J., and Roux, N. (2021). The social shortfall and ecological overshoot of nations. Nature Sustainability.

Laisser un commentaire